Progress Conference Reflections

On talent, apprenticeships, and progress

A few weeks ago, I spent three days in Berkeley having non-stop conversations about the present and the future. People were convinced that the future will look very different from the present. This was, of course, to be expected at a conference focused on renewing energy and enthusiasm for a new culture of progress.

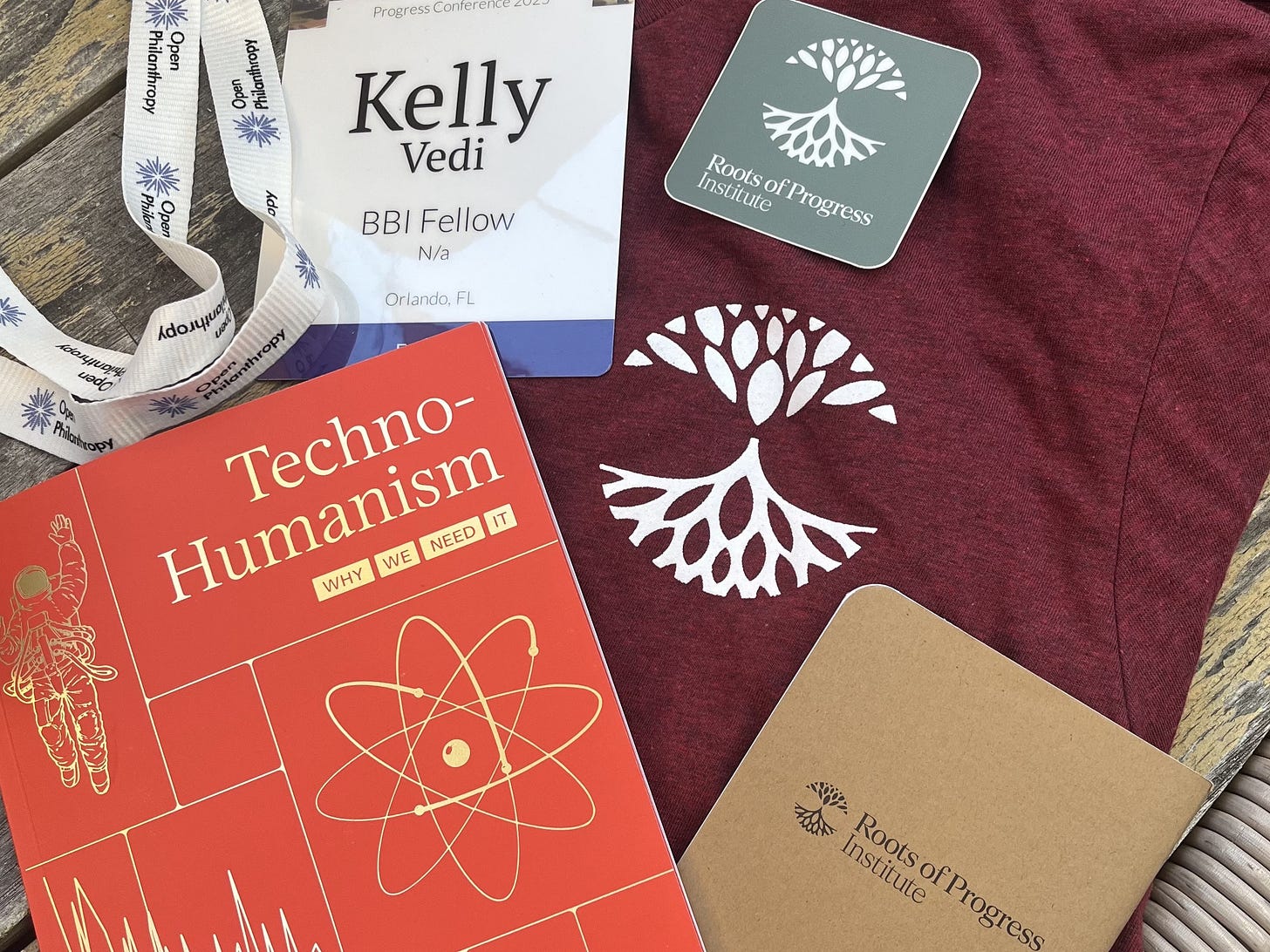

I was genuinely grateful to attend the Progress Conference as one of this year’s Roots of Progress Institute Fellows. It was great to finally meet the other fellows in person! They are an inspiring and enthusiastic bunch. I’m also deeply thankful to Emma McAleavy and Mike Riggs for all the support they gave us throughout the fellowship.

Part of the reason why I was so excited to be a part of the RPI Fellowship this year is because I wanted to bring the idea of apprenticeships to a new group of people. But, to be honest, I didn’t know if apprenticeships were a good ‘fit’ for progress studies. At the end of the conference, another RPI Fellow, Andrew Burleson, asked how I felt about that question now. With a few weeks distance, this post is my attempt to answer that question.

Beyond Outlier Talent

At the conference, I noticed that people were thinking about talent for sure. But many were mostly focused on identifying and cultivating outlier talent—the few individuals who might lead us to big breakthroughs. What seemed less discussed was how to expand broad-based skill acquisition. How can we raise the technical competence of society as a whole?

After I got home, I read an essay by Preston Cooper at AEI about the economic historian Joel Mokyr. Apparently, the recent Nobel-prize winner, attributes the technological progress of the Industrial Revolution to England’s broad use of apprenticeships. I wasn’t familiar with Mokyr’s work, but as I read, I kept nodding along. It connected neatly to what I’ve been thinking about apprenticeships and progress.

Cooper summarizes Mokyr’s argument like this:

“A few big names tend to dominate discussion of innovation during the Industrial Revolution—James Watt and the steam engine, Richard Arkwright and the water frame. But just as important… were the far greater ranks of skilled technicians and artisans who ‘were able to adapt, implement, improve, and tweak new technologies,’ tinkering until the novel machines ran far more efficiently.”

That line hit me. Cultivating outlier talent is great, but I think it neglects the fact that for these big breakthroughs to spread, we need people throughout society who are ready to implement and improve upon them.

Apprenticeships Produce Armies of Tinkerers

Mokyr’s research shows that the secret sauce behind England’s industrial success wasn’t formal schooling. It was apprenticeship.

He and his coauthors find that industrialization advanced fastest in regions with the highest density of apprentices. Two-thirds of the 759 “micro-inventors” they studied had been apprentices; only a quarter had gone to university. (Interestingly, this is about the same breakdown found in Switzerland today between young people who go the vocational versus academic route in high school.) Apprenticeships produced the engineers, millwrights, and mechanics who adopted and improved upon the ‘big’ technological innovations.

This aligns with what I’ve been thinking about progress studies and apprenticeships. If we want to progress, we need to be developing our whole society’s technical and applied skill base. And the way to do that isn’t to maintain our current schooling structure where kids sit in classrooms for years. It’s to get them into work environments where they can learn in an applied setting.

Let Reality Teach

For many kids, apprenticeships provide better structure and motivation than classrooms precisely because they are real, not artificial environments. In school, the teacher decides if you’re doing well. In work, the world tells you. You see whether your skills meet the actual demands of a workplace. Instead of hearing “you’ll need this someday,” you hear “I need this today.”

As Arun Rao notes in his write-up, there were a lot of conversations about the evolution of education at the conference. I especially enjoyed the conversations I got to have about the Montessori method. (And not just because my daughter recently started at a Montessori preschool…) Looking back at my notebook, there’s one line from another Fellow that I wrote down and circled - “Let reality be the arbiter.”

This is a phrase that captures an essential principle of the Montessori approach to education. In traditional education, the teacher is typically the arbiter who tells a student if they are right or wrong. By contrast, the Montessori method relies on concrete materials and a prepared environment so that reality itself can provide a child feedback.

Adherents to the Montessori method tend to have a lot of respect for what children are capable of. I see a similar attitude in apprenticeship advocates. We believe that young people can survive being subjected to reality. If we let them see how their performance, skills, and knowledge stack up to the demands of a workplace they’ll rise to the occasion.

And we shouldn’t make them wait until after four years of high school and four years of college to do so! In Switzerland, apprenticeships begin around age 16. I think that’s about right. At that age, most young people are ready to start the transition to adulthood. They’re eager for responsibility and capable of learning through doing. Maybe we should let them.

AI and the End of Skills?

You really can’t talk about the Progress Studies conference without talking about AI. One of the keynotes was Tyler Cowen interviewing Sam Altman, and attendees included folks from all the major AI companies. There were definitely some people at the conference who thought we were so close to AGI and maybe even superintelligence that skill acquisition wouldn’t even be an important problem anymore.

But, assuming skilled human labor continues to matter in the future, it’s clear that the pace of change in the workplace is picking up speed. And that’s why I think apprenticeships matter even more now. The pace of AI-driven change will make workplace evolution faster than any classroom can react to. Schools move on semester timelines; workplaces adapt in real time. That’s where young people should be learning.

Apprenticeships and Ambition

To finally answer Andrew’s question - I think apprenticeships are a good ‘fit’ for progress studies. But, I think that progress studies can be more ambitious when it comes to thinking about talent. We shouldn’t confine ourselves to focusing on how to identify and equip a small few. And there’s evidence that the community is open to this perspective. In reading other conference write-ups, I was delighted to learn that Joel Mokyr is well-regarded within the Progress Community. In fact, one attendee has already called for him to be a speaker at next year’s conference.

AI is going to impact nearly every corner of our economy to a greater or lesser degree. Apprenticeships offer a model for how to equip the vast majority of young people to gain the skills they need to contribute to the economy. If it worked for one technological revolution, maybe it will work for this one too.

Thanks for bringing "the idea of apprenticeships to a new group of people". A challenge that also needs to be addressed is the pressure put on students to attend college. Some of the pressure comes from peers and parents. The other source of pressure is the role high schools play in supporting a system that strongly encourages and awards college attendance (and in some communities costly private schools).

Apprenticeships can't be seen as a last resort for students that need more structure or don't test well. Career Day speakers don't include Union reps talking about their apprenticeship programs or a local electrician sharing their story. There's no flag to fly on your home or car bumper sticker to share a parent's pride in their graduate's choice of an apprentice program.

There is also a shortage (at least in the Middle Atlantic states) for talent in apprenticeship driven jobs. Some infrastructure exists for apprenticeship programs (unions/trades) but there's still work to be done building out high quality private sector programs and union partnerships to support the needs of a robust apprenticeship program. But there are opportunities to work with the existing programs and community colleges to bring the idea of apprenticeship to a new group of people.

Thanks